The Shows That Made the Decade

By Ian Jones, Chris Hughes, Graham Kibble-White, Jack Kibble-White, Steve Williams and TJ Worthington

First published December 2009

They may not have been the most watched, the most worthwhile, or even the most liked. But collectively they set the template for 10 years of television. They were the shows that defined the decade; the shows that established the tone of what made it on to the small screen, along with the names, places and formats that furnished the nation’s living rooms. If you’re looking for culprits to thank, or to curse, for the decade’s telly, read on.

John Hurt as Clark

The Alan Clark Diaries

(2003, BBC4)

The renaming of BBC Knowledge as BBC4 in 2002 wasn’t just a case of the Beeb tidying up its channel portfolio. It was to emphasise the fact that, rather than some digital outpost, the channel was now to be judged alongside BBC1 and BBC2 and would strive to match the wide mix of programming available on its more established brothers. Drama seemed a tough genre to mount on BBC4’s tiny budgets, but The Alan Clark Diaries showed one way forward. It used archive footage and readings from the titular book to add colour and atmosphere without breaking the bank.

Despite star John Hurt’s complaints about the low costs and intense schedules, the series pushed BBC4 ratings to a new high and was blessed with an almost immediate repeat on BBC2. BBC4 aped the approach for almost all its drama output during the rest of the decade. Biographies of icons were adapted to feature a big name in the title role. Fanny Cradock, Frankie Howerd and Kenneth Williams had their life stories revisited, starring Julia Davis, David Walliams and Michael Sheen respectively, while dramatisations of the lives of Harry H Corbett and Gracie Fields went on to win further record ratings.

Micro Men (2009), an account of the career of Sir Clive Sinclair, was a hugely enjoyable romp if somewhat atypical for eschewing the “tears behind the laughter” or “soft centre behind the hard exterior” formula. Yet all of these literary adaptations brought a bit of glamour and column inches to a channel that, though often reaching the highest standards, could sometimes seem to be rather forbidding.

![]()

Big Brother’s Little Brother

(2001-date, Endemol for E4)

Could there have been fanzine shows before Big Brother’s Little Brother? If so, what might they have been called? Bob Says Opportunity Knocked? Nationwider? Surprised, Surprised? As enticing as they sound, none would have worked. BBLB did work, and worked so well, thank to the notion that a popular television series could sustain its own introspective off-shoot. It was the first of its type and spawned so many imitations that the decade ended with the digital channel spin-off an integral to any blockbuster light entertainment, reality or drama series.

Presented with great affability by Dermot O’Leary (once he’d shaken off initial co-presenter Natalie Casey), the first few series of BBLB wheeled freely. They exploited all aspects of their parent as an excuse to produce great telly, often relying solely on items of their own invention to keep viewers entertained. They also knew exactly how reverential they should be to their source material, and unlike many of its successors the show never lost sight of the fact it should be inherently watchable and worthwhile in its own right.

In the deluge that followed, it often felt that the presence of a fanzine sibling helped gain the parent series a commission. After all, what other possible reason for a Mark Durden-Smith helmed spin-off other than that that it used the same studio, same crew and recycled much of the same material, thereby bringing down the average cost per airtime minute of any production and making projects that at first seemed prohibitively expensive, positively economic? Clearly never quite as good after O’Leary left to become emasculated on The X Factor (2004-date), it was still a shame BBLB would die in summer 2010 along with its parent.

![]()

Taransay, population: them

Castaway

(2000 & 2007, Lion Television for BBC1)

“An epic living project exploring how society could change in the future”. Or alternatively, stick 36 people on the Hebridean island of Taransay and see what happens. Castaway 2000 aimed fancifully high but was brought grubbily low. The fault was twofold: something the programme-makers should have seen coming (the free will of the show’s participants to wrangle over contracts and sell their stories to the press) and something they could never have expected (the success of Big Brother).

The former might not have proven so harmful had the latter not turned up halfway through the “living project” and diverted the nation’s attention from pre-filmed documentaries to as-it-happens, straight-to-camera actuality. Castaway 2000’s format mutated before the eyes of its dwindling audience and to the chagrin of its subjects. Believing viewers wanted immediacy and shock, the programme-makers ditched psychological profiling for webcams and confrontation. But ratings continued to slide. The grand finale comprised live coverage fronted by Julia Bradbury of participants leaving their island “homes” by helicopter.

The whole endeavour was a messy flop, but of a kind with which the BBC flirted shamelessly for the rest of the decade. There were successes, but only in children’s programming: Rule the School, Serious Jungle (both 2003) and, perhaps ironically, L&K Castaway (2001). Grown-up reality telly, such as 2001’s The Heat is On (14 people having their survival skills tested in Peru) or Fame Academy (2002-3), struggled be tangibly popular and demonstrably worthy. There was even a wretched revival in the shape of Castaway 2007 that, in its deployment of confession booths, contestants being voted off and a spin-off show on a digital channel, was as far removed in design from its namesake as its location, off the coast of New Zealand, was from Taransay.

![]()

Celebrity Love Island

(2005-2006, for ITV)

Washing up on our screens during perhaps the worst year ever for reality television (the class of 2005 also including Celebrity Wrestling and Celebrity Shark Bait), Celebrity Love Island was an underpowered version of Temptation Island, wherein a bevy of marginally famous people were whisked off to an exotic location where they were then left to do very little except sunbathe and, only if they really wanted to, flirt with each other a bit. It was a useful exercise only in so far as it taught ITV that being able to scrutinise celebs wasn’t of itself an entertaining or worthwhile experience.

Viewers required a little jeopardy or incident injected into the narrative. It also proved once and for all that, at their heart, celebrity-based reality shows relied on deprivation to get their kicks. This meant that audiences cared not one jot about Abi Titmuss supping a sambuca while resting by the pool. Indeed, the series only got interesting when a massive storm hit the eponymous land mass, bringing production to a complete halt.

The series wielded perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the moniker “Celebrity”. Were Love Island to return for a third series some time in the next decade, you can only hope it would at least arrive with the quaint but somehow far more pleasing prefix, “All Star”.

![]()

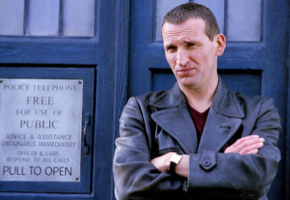

Doctor Who

(2005-date, BBC1)

There were three things you could count on any doom and gloom “media commentator” muttering in the first half of the decade: that broadcasters were terrified of taking risks, that genre and “event” television had been all but eradicated by bland and homogenous programming, and that nobody bothered watching on a Saturday night any more. While there was more than a grain of truth to all of these accusations, nobody would have bet on the charge against them being led by a revival of a show that had limped out in 1989 with next to no fanfare.

Even Doctor Who’s famously obsessive fanbase seemed warily muted about the chance of successful comeback. Yet almost from the opening moments, the revival captured a mass audience’s imagination in a manner that little else had managed for many years. The new series of Doctor Who helped revive a long-abandoned tradition for Saturday evening family drama, as witnessed by successive BBC1 efforts Robin Hood (2006-8) and Merlin (2008-date), besides legitimising programmes with a science fiction tinge. Life on Mars (2006-7), Primeval (2007-date) and Doctor Who adult spin-off Torchwood (2006-date) were fast-tracked into production after years of languishing in “development”.

Opinions as to the merits of the revived Doctor Who itself may vary wildly (though arguably the only opinion that really carries any real weight is that of the mainstream audience at which it is aimed), but there can be no denying that it left audiences with a lot more TV from which to choose.

![]()

Punk to classical music conductor

Faking It

(2000-2005, RDF Media for Channel 4)

In the 1990s Stephen Lambert had overseen the BBC1 docusoaps The Clampers and Lakesiders. His first project of the new decade was even more simple: a real-life replay of Pygmalion. The first episode of Faking It challenged privately educated 20-year-old Alex Geikie to pass himself off as a bouncer. But there was a twist. Geikie was gay, and his agonising over whether or not to come out to his mentors felt like genuine drama. It seemed that unscripted “ordinary” people could create TV gold when placed in a contrived environment.

A further 47 episodes of Faking It duly aired, as punk rocker turned classical conductor, rugby jock became drag queen and, in the last ever installment, a physicist tried out as a magician. The show won dozens of awards and inspired an equal number of successors, mostly confined to Channel 4. Lambert himself rustled up Wife Swap (2003-9) and The Secret Millionaire (2007-date), while other shows opted to inject “TV people” into everyday life, such as Supernanny, It’s Me or the Dog and How Clean is Your House?

Cheap, repeatable and easily to sell as a social experiment, the “formatted documentary” became ubiquitous. But in doing so it also became exhausted. Its simplicity could not supply it enough stamina, and manipulation appeared increasingly a substitute for imagination. Boundaries blurred with reality television, and soon all notion of social experimentation was laughable. It was all over bar the shouting. And there was a lot of that. In 2009 Wife Swap and How Clean is Your House? were axed. Struggling for funding and frantic to emphasise its public service credentials, the network ended the decade cauterising these former hits turned carbuncles.

![]()

Kevin McCloud in the house

Grand Designs

(1999-date, Talkback Thames for Channel 4)

When designer Kevin McCloud first reported on the progress of a timber frame kit house in Newhaven, East Sussex, nobody realised he was placing a flag in the ground to claim new, abundant territory for television. Home improvement shows were in the ascendant by the late 1990s, Changing Rooms and Homefront tutoring viewers to become more aspirant about how and where they lived. But Grand Designs proved the very process of building a house made for involving TV.

It was followed two years later by Location, Location, Location which, though less obviously televisual, found an involving narrative in people looking for their next house, besides tapping directly into a rising cultural obsession for property prices. Two months later the triumvirate was completed by Property Ladder.

A mass land grab now took place. Property shows spilled into daytime schedules on BBC1 and ITV1, while C4 attempted to expand their portfolio with short-lived vehicles for Naomi Cleaver: Other People’s Houses (2001) and Honey I Ruined the House (2004). ITV1 even tried to push the genre into primetime with the Ulrika Jonsson-fronted Home on Their Own in 2002 (kids redesign mum and dad’s house) and the blisteringly bad Saturday night effort Design Wars (2003) hosted by, of all people, by Mark Durden-Smith and Ann Maurice. By the decade’s close C4’s property portfolio had been augmented by the arrival of The Home Show (2008) and was responding deftly to the recession with spin-offs such as Property Ladder: Snakes And Ladders. This boom isn’t over yet.

![]()

Going local

The League of Gentlemen

(1999-2002, BBC2)

The four-man comedy team of Jeremy Dyson, Mark Gatiss, Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith had enjoyed one moderately successful series on BBC2 in 1999. Then, early in the new decade, they unveiled a macabre new character who took an unsuspecting audience by surprise and which helped propel The League of Gentlemen to commanding heights. Papa Lazarou was just one component of an expertly-judged second series that straddled the line between comedy and horror and restraint and excess.

By the end of 2000 the formula had taken the cult performers to the level of Christmas tie-ins and sell-out tours. But another consequence was that “dark” became fashionable, and not just in comedy series such as Channel 4′s jam (2000), Green Wing (2004-7) and Peep Show (2003-date). During the next few years it was possible to detect a bleaker tone infect everything from drama to music shows. Little of these efforts boasted the panache of the show that started it all. When Channel 4 broadcast a live autopsy in 2002, it was almost grimness and explicit gore for the sake of it.

Yet even The League of Gentlemen lost its way a little. The third and final series in 2002 seemed to value cruelty and shock above any tangible “jokes”. It was telling that two of the biggest comedy successes of the second half of the decade, The IT Crowd (2006-date) and Gavin and Stacey (2007-9), were conceived as a contrast to “dark” humour; while 2009’s Psychoville, a sitcom by two former Gentlemen, kept shock value very much secondary to funny material.

![]()

"Free love on the free love freeway"

The Office

(2001-2003, BBC2)

The naturalistic spoof-documentary sitcom People Like Us ran for two series between 1999 and 2000. A third series was planned, before BBC2 Controller Jane Root decided instead to commission a new comedy of similar style but based in just one location: The Office. But while the star of People Like Us, Chris Langham, was a comedian of 20 years’ TV experience, the lead in The Office, Ricky Gervais, was a virtual unknown. Root’s decision very quickly paid off for the BBC, as the new show became a runaway success.

It eclipsed the more energetic and exaggerated comedy of The League of Gentlemen and Spaced (1999-2001) with its more subdued and understated approach, coupled with acute observations of workplace life. But it was the tone of The Office more than anything that would prove so influential. Some programmes, such as Peep Show and The Thick of It (2005-date), managed to apply aspects of the style of The Office to create similarly solidly-conceived takes on recognisable aspects of life. A great many others, including The Robinsons (2005), The Last Chancers (2002), and the mangled adaptation of superior radio comedy Absolute Power (2003-5), merely slapped a “naturalistic” feel on to scripts for which it wasn’t suited or that weren’t up to scratch to begin with.

Come the end of the decade there still existed a steady stream of copyists that looked about as “fresh” in comparison to The Office as Up Sunday did to That Was the Week that Was.

![]()

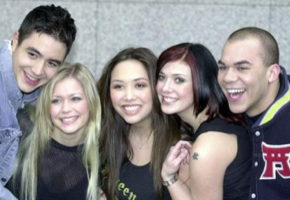

Popstars

(2001-2002, LWT for ITV)

With hindsight it seems almost unbelievable that auditionees were allowed to strut their stuff in front of storage heaters and that culls of contestants were announced in what appeared to be a Travelodge Hotel conference room. Viewed almost a decade on, Popstars betrays not only a constrained budget but also a singular absence of environmental control. Yet although its successors smartened up the format, the core ingredient of Popstars survived the decade intact: a distillation of reality.

The modern iteration of the talent show began from a place that owed as much to documentary as to light entertainment. As the years went by, this reality became heightened; first Pop Idol, then The X Factor and Britain’s Got Talent filtered out anything that wasn’t depicting tension, outrage or devastation. The format travelled a long way from footage of finalists practising their big number in the bogs. Popstars was a grab-bag concoction, containing all the parts necessary for a killer show plus other elements that, like those less accomplished vocalists, got culled along the way as the formula evolved.

Some good stuff, such as the judging panel and the sequences of terrible auditionees, endured. Sadly, the really good stuff – shots of people hanging around, footage of the winning act embarking upon their career – has long since gone, ushered out by the grand judges of programme-making with scarcely a consolatory farewell of: “I’m sorry it’s the end of the line for you”.

![]()

Sharpening the knives

Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares

(2004-2009, Optomen for Channel 4)

Rancid scallops were central to Gordon Ramsay’s accession into Channel 4 royalty. Weeks before the debut of Kitchen Nightmares, viewers were treated to trailers featuring the chef chucking up the spoilt seafood. When the series did eventually “rock up” (a phrase of which its host became vocally fond), Ramsay was at the pub-cum bistro Bonapartes in Silsden, Yorkshire. The sheer ineptitude of chef Tim Gray, coupled with Ramsay’s expletive-strewn responses, gave the show a distinct, charged atmosphere.

Little wonder its working title was changed from “Restaurant Rescue” to the more heightened “…Nightmares”. This was the traditional “troubleshooter” TV format turned into a battle between victims and a hero who you could both root for and fear. As usual, other channels were quick to ape its success. Five sent its own no-nonsense, fiery-mouthed expert Ruth Watson to the pits of the hospitality industry in The Hotel Inspector (2005-date), only for Watson to defect to C4 to front Country House Rescue (2008-date) and Ruth Watson’s Hotel Rescue (2009-date). Another no-nonsense, fiery-mouthed expert, Mary Portas, eviscerated failing retail businesses for BBC2 in Mary Queen of Shops (2007-date).

But Ramsay grew restless. He wearied of his foes’ attempts to out-smart him, then decided to pull the plug, explaining: “If the restaurants succeed, there’s no praise. If they’re screwed, we’re blamed and get lawyers’ letters.” His doppelgangers, however, pressed on. Watson, her successor on Five, Alex Polizzi and Portas marched into the new decade pointing their fingers and guiding us on to a better future. There was to be no let up from this nightmare.

![]()

In the front room

The Royle Family

(1998-2008, BBC2 & BBC1)

Only one series of The Royle Family was broadcast during this decade, and was by some distance the weakest of them all, but its influence was vast. It shared a low-key nature and lack of laugh track with The Office while simultaneously popularising Northern whimsy and a warmth of character. The work of Peter Kay, most obviously Phoenix Nights (2001-2), owed much to Caroline Aherne’s creations and was again unashamedly regional.

Throughout the decade a repertory company of sorts emerged from these series. The likes of John Henshaw, Mark Benton, Janice Connolly and Steve Edge popped up in a variety of settings, often playing similar characters. Edge often specialised in gormless bluffers, Henshaw long-suffering father figures. Among the shows that owed much to the Royles were Dead Man Weds, Dave Spikey’s take on provincial newspapers; Craig Cash’s pub-set Early Doors; the unashamedly working class Benidorm; Thin Ice, a tale of warring ice skating teams; and The Visit, centred on a prison. Even The Cup, an adaptation of a Canadian series, fitted perfectly in this genre, helped by the presence of Steve Edge (again) and one episode being filmed that famous Peter Kay haunt, Bolton Services.

Some of these series specialised in comedy that was so low key as to be barely noticeable. But even if the jokes seemed to revolve forever around breaking wind and Cillit Bang, the acting was normally first class. Plus it was nice to see the north of England’s fine comedy performers with an alternative to Last of the Summer Wine as their pension.

![]()

Spooks

(2002-date, Kudos Productions for BBC1)

In the second week of September 2001, the idea of a primetime drama featuring MI5 battling al-Qaeda and other assorted baddies in a London in seemingly weekly peril from dirty bombs or chemical warfare might have been a difficult sell. But Spooks’ debut was less than 12 months after 9/11, and the series went on to present a hi-tech, heightened-reality take on a decade of threat, from the so-called “war on terror” through 7/7 to the brink of global financial collapse.

Infamously, the show revealed its hand in only its second episode, when Lisa Faulkner’s character, hitherto promoted as an integral member of the team, was killed off after having her face plunged into boiling oil. The programme’s credo of “anyone can die at any time” has seen seven lead characters bumped off to date and was imitated shamelessly by Torchwood and the rebooted Survivors (2008).

Meanwhile the ever-shifting cast served to bring Peter Firth, quietly excellent as Harry Pearce, front and centre, establishing the Section D head as the moral pillar of the piece amid a succession of self-serving British politicians and the CIA, naturally, depicted as brash and interfering. If Spooks relied sometimes too hard on cut-out rogue Russian oligarchs and ruthless Serbian hitmen, at least it never made the mistake of playing it with anything other than a straight face (for how not to do it, see the first two series of Torchwood). And occasionally its scripts proved scarily prescient. One episode filmed before 7/7 and broadcast just two months later featured an attempted terrorist attack on London, and an episode screened in November 2008 depicted Britain’s economy in meltdown, at a time when it appeared the same thing was happening in real life.

![]()

Roll-call!

Teachers

(2001-2004, Tiger Aspect Productions for Channel 4)

Bawdy provincial ensemble drama series threaded their way through the decade. Teachers established the mould: a group of characters who drift through a drab existence alternately shouting and having sex. The banality was spiced up by the casting of faces that were familiar, but not famous, and who could be superseded as years went on. So while Andrew Lincoln was the ostensible star of Teachers, he was not the “lead”; the show was not his vehicle, and indeed went out to outlive him.

The formula was a popular and successful one for Channel 4, inspiring No Angels (2004-6) and Shameless (2004-date), with the same concerns transposed respectively to nursing and a working class council estate. Shameless became an enormous hit but ended up more a brand than a serial, its early potency diluted by a continually evolving cast and increasingly unsubtle storylines. This evolution was duplicated by Skins (2007-date), another ribald brew with a seemingly renewable cast list but aimed at teenagers and first shown on E4.

Similarly earthy approaches to primetime drama were evident on other channels, such as BBC1’s Clocking Off (2000-3) and Linda Green (2001-2), while more exaggerated manifestations of decadence were the focus of BBC1’s Hotel Babylon (2006-date) and ITV1’s Bad Girls (1999-2006) and Footballers’ Wives (2002-6).

![]()

Top Gear

(Current series: 2002-date, BBC2)

Top Gear used to be a bit of a joke. Fronted by William Woollard with his foot resting on the bumper of the new Ford Scorpio, it featured test drives (“Let’s see how she handles out on the open road!”), the unctuous Quentin Willson hunting for bargain hatchbacks, and, of course, Clarkson. Not the sort of programme that looked like the basis for a global television phenomenon. The series was scrapped in 2001 having lost most of its personnel to Five.

Then Jeremy Clarkson, who had departed in 1999, and producer Andy Wilman, pitched a new format to the BBC. They adhered to the blueprint used by Chris Evans in creating TFI Friday, building the show on regular features that could become brands in their own right: Star In A Reasonably Priced Car, The Stig and a succession of challenges and races, setting the whole thing in a hangar full of punters standing around. In this guise Top Gear returned in 2002 fronted by Clarkson, motoring journalist Jason Dawe and the puppyish Richard Hammond. But it wasn’t until Dawe was jettisoned in favour of the affected fogeyism of James May that the classic triumvirate was completed, establishing a trio that competed with and against each other in a series of ever-more ambitious challenges.

Few shows of the decade were made with more care and attention. Every shot would be framed and filtered to perfection, with one film reportedly taking 33 days to edit. Other channels attempted to replicate the formula (BBC2’s Full On Food, Five’s The Gadget Show) but Fifth Gear, fronted by the original Top Gear team, was scrapped in 2009. Meanwhile both Hammond and May became stars in their own right fronting spin-offs such as May’s heart-lifting series of life-sized toy challenges. None of Top Gear’s success happened without controversy. The evolution of Clarkson’s character from middle-aged man at odds with the world to tiresome boor was depressing to witness, and it remains to be seen how long the trio can head off the forces of diminishing returns. But for now, as long as people claim they don’t like cars but love Top Gear, it seems set to stay on Sunday nights.